The Quick Answer (For When You’re Procrastinating on Reading This)

I stared at a ‘26.2’ magnet on my whiteboard for three years.

Every January, I’d write ‘Run a marathon’ at the top of my goals list. Every December, it was still there—untouched, mocking me. I had the shoes, the training plans, the knowledge. What I didn’t have was the one thing that actually mattered. The satisfaction from actually doing one.

Here’s what I learned: The real reason you procrastinate isn’t laziness or poor time management—it’s that you’re waiting for conditions that will never exist. The gap between “I want to” and “I did” isn’t about readiness or preparation. It’s about willingness.

The Solution from this essay in 3 Bullets:

- Stop asking “Am I ready?” Start asking “Am I willing?”—willing to do it badly, willing to fail, willing to suffer through it?

- Use the Reversal of Desire tool – Change your relationship with discomfort by saying “bring it on” instead of avoiding pain.

- Just start imperfectly – The underwhelming reality of doing something beats the perfect imagination of planning it.

What You’ll Learn in this post:

The psychology behind why smart people procrastinate, the “Impossible Bar Syndrome” that keeps you stuck, a practical tool from behavioral psychology that changes your relationship with resistance, and the exact framework I used to finally complete goals I’d avoided for years.

The Marathon I Never Ran (Until I Walked Out My Door Unprepared)

I stared at that ‘26.2’ magnet on my whiteboard for three years. Every January, I’d write ‘Run a marathon’ at the top of my goals list. Every December, it was still there—untouched, mocking me.

I had the shoes, the training plans, the knowledge. I even did 10Ks and committed to running a mile every day. But that bigger goal? It just sat there, year after year.

I was pursuing becoming the type of person who knows how to do a marathon. It was a consumer mindset—if I had all the things marathoners had, somehow it would get done. But having all the pieces doesn’t complete the puzzle. Only action does.

I’d set it up as this massive thing that required perfect training, perfect conditions, perfect timing. So it never happened because the conditions were never perfect. I was waiting for the right moment that never came.

Then one cold morning, I stopped waiting. I stopped planning.

I just walked out my front door—I hadn’t eaten, hadn’t trained, didn’t stretch, hadn’t signed up for anything. No water, no nutrition, no plan. Just pure decision: today’s the day.

I was out there all afternoon, all the way into the sunset. I took every path and road from my neighborhood I could find. And I just didn’t stop until I had done a marathon.

That walk was brutal. I was 320 pounds at the time, and it was rough on my knees. My legs were screaming, my mind was fighting me, but I kept going.

Around mile 20, I remember crying a bit when I made it back to my house. (Listen, you would have cried if you were there LOL). I realized I had calculated my route wrong—I was short 2-3 miles. I could see my apartment right there, but I had to circle the lake in front of it, my feet blistered and hurting.

It was so discouraging. I just wanted to be done. But I kept going.

The time wasn’t impressive. My fitness wasn’t impressive. But none of that mattered. What mattered was that I finally finished it.

Something changed in me that day. I realized the avoidance wasn’t about the marathon itself—it was about the fear of committing to something that scared me in the present.

As long as I never tried, I could tell myself I could do it if I wanted to. But actually doing it, suffering through it, pushing past the point where everything in me wanted to quit—that showed me something real about myself.

I learned that the voice telling me to quit isn’t the truth about my limits. It’s just noise, patterns of thoughts with no weight. And I learned that finishing something hard matters more than how impressive the finish looks.

Since that first marathon, I’ve run three or four more. Ones where my watch died, ones where I had to lay down halfway through and didn’t finish until 3 AM. But not that first one. Not anymore. It’s done.

It was all mental. Once I knew I could do it, you couldn’t get me to stop.

I’m not a fitness junkie. I’m someone who tries to do things when I’m not ready, when I’m not sure if I have what it takes. And more often than not, I don’t have what it takes. I’ve failed my 100-mile bike ride.

I’ve fumbled the ball in a lot of areas.

But here’s what I know: The underwhelming reality is going to mean infinitely more to you than the perfect imagination. Being in the arena is so much more fulfilling than sitting in the stands, no matter how badly you think you’re losing.

Why Smart People Procrastinate (And Why You’re Not Lazy)

Here’s what I’ve learned after years of watching myself and working with other people on this: you’re not procrastinating because you’re lazy or undisciplined. You’re procrastinating because you’re smart enough to imagine all the ways something could go wrong.

The research backs this up. Dr. Tim Pychyl, who’s been studying procrastination for over 25 years, defines it as “the voluntary delay of an intended action, despite expecting to be worse off for the delay.”

Notice what’s missing from that definition? Laziness. Poor time management. Lack of willpower.

What’s actually there? Voluntary delay. You’re choosing to delay, even though you know it’s going to make things worse.

Why would anyone do that?

It’s Not a Time Management Problem—It’s an Emotion Regulation Problem

Here’s where things get interesting. As Pychyl explains, “Procrastination is not a time management problem. Time management may be necessary for our success, but it’s not sufficient.”

I know this firsthand. I’m actually pretty good at time management—I’ve been using a calendar for decades, tracking everything down to the minute. But that didn’t stop me from procrastinating on that marathon for three years.

The real issue? Procrastination is an emotion regulation problem.

Dr. Fuschia Sirois, another leading procrastination researcher, frames it this way: “Procrastination is a result of prioritizing short-term mood regulation over long-term goals.”

When you face a task that triggers uncomfortable emotions—fear, self-doubt, perfectionism, overwhelm—your brain prioritizes feeling better right now over achieving your goal later.

This is what researchers call “giving in to feel good.” As Pychyl explains, “We are, in effect, giving in with our procrastination to feel good, and it undermines our goal pursuit and well-being.”

Think about it: when you avoid that important task, you get immediate relief from those uncomfortable feelings. Your brain says, “Ah, much better!” But here’s the problem—those feelings don’t actually go away. They just get delayed, and they come back stronger.

The Three Ways Smart People Get Stuck

1. Impossible Bar Syndrome (The Perfectionist’s Trap)

I call this “Impossible Bar Syndrome” because I’ve done it so many times myself. You set the bar so impossibly high that you can never actually start.

For me, the marathon needed perfect training, perfect conditions, perfect timing. I needed to be the “right” weight, have the “right” gear, follow the “right” plan.

But here’s what I’ve learned: Setting the bar too high is just sophisticated procrastination.

As Dr. Joseph Ferrari notes, “Perfectionism has a significant relationship with procrastination, with non-procrastinators being perfectionistic to excel and procrastinators being perfectionistic to fit in.”

The difference? Non-procrastinators use perfectionism to push themselves forward. Procrastinators use it as an excuse to never start.

I was definitely in the second camp. I’d start training plans, get a few weeks in, and then convince myself I wasn’t doing it “right.” So I’d stop, research more, buy more gear, and find a “better” plan.

It was a consumer mindset—if I had all the things a marathoner had, somehow it would get done.

But having all the pieces doesn’t complete the puzzle. Only action does.

2. Fear of Breaking the Perfect Vision

Here’s the sneaky part: as long as I never tried, I didn’t have to break that vision in my mind that I could just do it.

This is what researchers call “temporal discounting”—we prefer immediate comfort over future reward. Your present self wants to feel good now, so it treats your future self like a stranger who can deal with the consequences later.

As Pychyl explains, we “prefer tomorrow over today because we rely on present feelings to predict the future” and we treat our future selves like strangers.

The problem? Your future self is still you. And when tomorrow becomes today, you’re still the same person who didn’t want to do it yesterday.

But there’s another layer here: protecting your identity and self-image.

If you never try, you never have to face the possibility that you’re not as capable as you think. You can maintain the fantasy that you could do it if you really wanted to.

I spent years telling myself I could run a marathon if I just trained properly. But deep down, I was scared that if I actually tried and failed—or even if I succeeded but it was messy and unimpressive—it would shatter that image.

3. The Voice That Tells You to Quit (And Why It’s Just Noise)

That voice in your head that says “I don’t want to. I don’t feel like it. I’ll feel more like it tomorrow”?

Pychyl calls this “the Procrastinator’s Song.” And here’s what’s wild: that voice isn’t truth—it’s just patterns of thoughts with no weight.

When I was out there walking that marathon, my mind was screaming at me to quit. My legs were on fire. I was exhausted. Everything in me wanted to stop.

But I learned something crucial: those thoughts are just thoughts. They’re not commands. They’re not predictions. They’re just noise.

As Steven Pressfield writes in The War of Art, “Procrastination is the most common manifestation of Resistance because it’s the easiest to rationalize. We don’t tell ourselves, ‘I’m never going to write my symphony.’ Instead we say, ‘I am going to write my symphony; I’m just going to start tomorrow.'”

The voice gets louder right before breakthroughs. It’s not a sign you’re on the wrong path—it’s a sign you’re on the right one.

Is Procrastination the Same as Laziness?

No. And this distinction matters.

Laziness is a lack of motivation or energy. Procrastination is actively avoiding something you want to do because of the emotions it triggers.

As Mark Manson puts it bluntly: “Every problem of self-control is not a problem of information or discipline or reason but, rather, of emotion. Self-control is an emotional problem; laziness is an emotional problem; procrastination is an emotional problem.”

You’re not lazy. You’re emotionally avoiding something. And that’s a completely different problem with a completely different solution.

Can Procrastination Ever Be Good?

Here’s my take: Not really, but some delays aren’t procrastination.

Pychyl makes an important distinction: “Although all procrastination is delay, not all delay is procrastination.”

There’s a purposeful delay (choosing to do something more important first). There’s an inevitable delay (life happens—sick kids, late planes, emergencies). There’s a delay due to emotional problems (grief, depression—these need to be addressed separately).

But actual procrastination? The voluntary delay despite expecting to be worse off? That’s never helpful.

As one researcher sums it up: “Procrastination is usually harmful, sometimes harmless, but never helpful.”

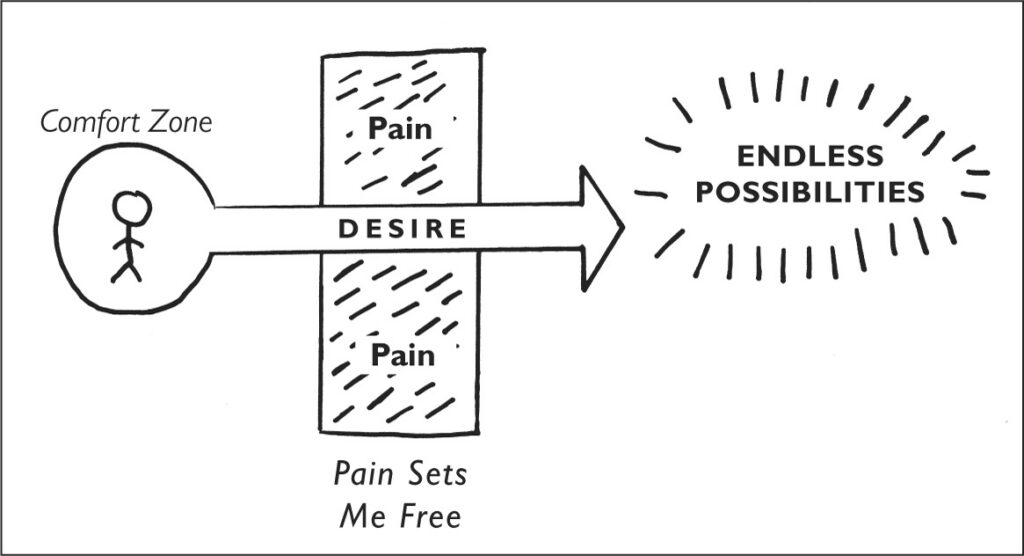

The Reversal of Desire: A Tool to Change Your Relationship with Discomfort

After that first marathon, I discovered a tool from a book called The Tools by Phil Stutz and Barry Michels that I wish I’d known about years earlier.

It’s called the Reversal of Desire, and it’s designed to help you move toward things you’re avoiding instead of running away from them.

The Core Principle: The pain of avoiding something you want is always worse than the pain of actually doing it. This tool changes your relationship with discomfort so that pain becomes a reason to keep going instead of a reason to stop.

As Stutz explains, “Pain is not absolute. Your experience of pain changes relative to how you react to it. When you move toward it, pain shrinks. When you move away from it, pain grows. If you flee from it, pain pursues you like a monster in a dream. If you confront the monster, it goes away.”

How the Reversal of Desire Works

The tool has three steps. Here’s the exact process from a book called The Tools:

Step 1: “BRING IT ON!”

See the pain appear in front of you as a cloud. Scream silently at the cloud, “BRING IT ON!” Feel an intense desire for the pain to move you into the cloud.

The key here is to make the pain as extreme as you can. What would it feel like if you got the very worst outcome? If you can master the worst, then anything less becomes easy. The more intense the pain—and the more aggressively you move into it—the more energy you’ll create.

Step 2: “I LOVE PAIN!”

Scream silently, “I LOVE PAIN!” as you keep moving forward. Go so deeply into the pain you’re at one with it.

You’re not desiring pain because you’re masochistic; you’re desiring pain so you can shrink it. When you become confident you can do this every time, you’ve mastered your fear of pain.

Step 3: “PAIN SETS ME FREE!”

You will feel the cloud spit you out and close behind you. Say inwardly with conviction, “PAIN SETS ME FREE!” As you leave the cloud, feel yourself propelled forward into a realm of pure light.

This is the Force of Forward Motion. By moving through discomfort instead of avoiding it, you experience a burst of energy that comes from taking action. You’re free from the avoidance pattern.

When to Use It

Stutz identifies two key cues:

Cue 1: Right before you’re about to do something you want to avoid.

Let’s say you have to call someone who intimidates you, or you really need to get down to work, but you feel restless and distracted. At these moments, focus on the exact pain you’d feel if you began the action. Use the tool on that pain (multiple times if necessary) until you can feel the energy of the final step carrying you forward. Don’t stop to think—let it lead you right into taking the action you were avoiding.

Cue 2: When you catch yourself thinking about the dreaded task.

We all share the same bad habit. When we have to do something we find extremely unpleasant, we start thinking about it rather than doing it: “Why do I have to do it? I can’t do it, I’ll do it next week,” etc.

Thinking can’t help you act in the face of pain; in fact, it usually makes you even more avoidant. The only way your thoughts can help you master pain is if they trigger you to use the Reversal of Desire.

Each time you catch yourself thinking about the dreaded task, stop thinking and use the tool.

What It Doesn’t Do (And Why That’s Actually Good)

This doesn’t make the pain go away. It just changes your relationship to it.

Instead of pain being the reason to stop, it becomes fuel to keep going.

I use this tool now whenever I feel that familiar pull to avoid something that I know I need to do. When my legs are screaming during a run, when I want to quit a project that matters, when I’m scared to have a difficult conversation—I use the Reversal of Desire and I remember that those thoughts are just thoughts. That I can take over the narrative using this tool.

Readiness Is a Myth (Willingness Is Everything)

I’m going to tell you something that might be hard to hear: You’re never going to feel ready.

Not for the marathon, not for the business, not for the conversation, not for any of the things that scare you.

But you know what? You don’t need to be ready. You just need to be willing.

The Core Reframe: The gap between “I want to” and “I did” isn’t about readiness, preparation, or having the right plan. It’s about decision. It’s about willingness.

The Three Questions That Matter

Instead of asking “Am I ready?” ask yourself:

1. Am I willing to do it badly?

Your first attempt will be messy. My time wasn’t impressive. My fitness wasn’t impressive. But none of that mattered.

What mattered was that I finally did it.

Give yourself permission to be bad at something initially. Get it out there. You can always improve later.

Bonus: You might also catch something beautiful, like the sunset I saw the night I did my marathon.

2. Am I willing to fail?

I failed my 100-mile bike ride. I’ve largely fumbled the ball in a lot of areas going from being a freelance marketing consultant behind the scenes to trying to bring myself out into the public.

But here’s what I’ve learned: Being in the arena is so much more fulfilling than sitting in the stands, no matter how badly you think you’re losing.

Every failure in reality teaches you something that infinite success in imagination never could.

3. Am I willing to suffer through it?

Physical discomfort (legs screaming, mile 20 breakdown). Mental discomfort (calculations wrong, emotional breakdown).

The suffering is the point—it proves something to yourself.

As Mark Manson writes, “When we deny ourselves the ability to feel pain for a purpose, we deny ourselves the ability to feel any purpose in our life at all.”

You never feel ready. But you do have right now. And the opportunity right now.

The Underwhelming Reality Beats the Perfect Imagination

Here’s what I know now: The underwhelming and disappointing reality is going to mean infinitely more to you than the imagination in your mind.

The imagination keeps you comfortable. The reality teaches you who you are.

Every failure in reality > infinite success in imagination.

The 4-Step System to Stop Procrastinating (Starting Today)

Okay, enough theory. Here’s exactly what to do when you catch yourself procrastinating on something that matters.

Step 1: Identify What You’re Actually Avoiding

Write down the goal that keeps showing up year after year. Ask yourself: “What am I really afraid of here?”

Distinguish between legitimate preparation and sophisticated avoidance.

Diagnostic Questions:

- Have I been “preparing” for this for more than 3 months?

- Do I have everything I need to start a messy version?

- Am I waiting for conditions that may never exist?

If you’ve been “preparing” for months without actually starting, you’re probably procrastinating. If you have everything you need to start a messy version, you’re probably procrastinating. If you’re waiting for perfect conditions, you’re definitely procrastinating.

Step 2: Lower the Bar to “Just Start”

Remove ALL conditions. Define the smallest possible first action. Give yourself permission to do it badly.

Example Framework:

- Marathon → Walk around the block

- Business → Register the domain

- Book → Write 100 bad words

- Conversation → Send the text asking to talk

I didn’t eat. I didn’t train that morning. There was no stretching. I didn’t sign up for anything. I just walked out my front door.

That’s it. That’s the bar. Just start.

Step 3: Use Reversal of Desire in Real-Time

When you feel the resistance, use this exact script:

- Name it: “I’m feeling the urge to quit”

- Invite it: “BRING IT ON! I want this discomfort.”

- Welcome it: “I LOVE PAIN! This challenge is setting me free.”

- Recognize: “PAIN SETS ME FREE! This is the Force of Forward Motion.”

Repeat it multiple times if necessary. Don’t stop to think—let it lead you right into taking the action you were avoiding.

Step 4: Prove It to Yourself Once

One completion changes everything. You only need to prove capability once. Momentum becomes self-sustaining.

What Success Looks Like: The time wasn’t impressive. My fitness was not impressive. But none of that really mattered. It just mattered that I finally decided to do it, and I did.

The Pattern Shift: Since that first marathon, I’ve ran three or four more. Once you see you can do it, you just couldn’t get me to stop. Not because I’m a fitness junkie but because I’m trying to do things when I’m not ready.

“But What If…” (Your Questions Answered)

Q: What if my goal actually requires preparation? (Marathon training, business plan, etc.)

A: Here’s the distinction: Minimum viable preparation vs. perfectionist delay.

If you’re training for a marathon, you do need some preparation. But you don’t need a perfect 16-week plan, the perfect shoes, the perfect route, and perfect weather.

You need: shoes (any running shoes), a route (your neighborhood works), and to start (today).

The same applies to a business. You don’t need a perfect business plan, the perfect website, the perfect branding. You need: an idea, a way to deliver it, and to start (today).

The rule of thumb: If you’ve been “preparing” for more than 3 months without actually starting, you’re probably procrastinating.

Q: How do I know if I’m avoiding something or if it’s genuinely not the right time?

A: Here’s the decision framework:

You’re probably avoiding if:

- You’ve been saying “I’ll do it when…” for more than 3 months

- You keep researching and planning but never starting

- You’re waiting for conditions that may never exist

- You feel guilty or anxious when you think about it

It might genuinely not be the right time if:

- There’s a legitimate external barrier (health issue, financial constraint, etc.)

- You’re in the middle of a crisis that needs your attention

- You’ve tried multiple times and failed for the same specific reason

But here’s the thing: Even if it’s “not the right time,” you can usually take one tiny step. Register the domain. Write 100 words. Walk around the block.

Q: Isn’t some planning and analysis valuable? How much is too much?

A: Yes, some planning is valuable. But here’s the line: Planning helps when it leads to action. Planning is avoidance when it replaces action.

The “3-month rule”: If you’ve been planning for more than 3 months without taking action, you’re probably avoiding.

As Pychyl notes, “95–98% of procrastination is getting started.” The solution isn’t more planning—it’s specifying the very next concrete action and scheduling it.

Q: What if I start and fail spectacularly?

A: I failed my 100-mile bike ride. I’ve largely fumbled the ball in a lot of areas.

But here’s what I’ve learned: Failure is data, not identity.

Every failure teaches you something that success never could. The arena is better than the stands, even when you’re losing.

As I wrote earlier, “The underwhelming and disappointing reality is going to mean infinitely more to you than the imagination in your mind.”

Q: How is this different from just “pushing through” or toxic positivity?

A: Great question. Here’s the distinction:

Toxic positivity says: “Just think positive! It’s not that bad! You can do it!” (This ignores legitimate pain and can be harmful.)

Reversal of Desire says: “This is hard. This hurts. And I’m going to move toward it anyway because the pain of avoiding it is worse.” (This acknowledges the pain and changes your relationship to it.)

“Pushing through” often means ignoring your body’s signals and can lead to burnout.

Reversal of Desire means acknowledging the discomfort, accepting it, and using it as fuel rather than letting it stop you.

The key difference: You’re not ignoring the pain. You’re transforming your relationship to it.

What Are You Avoiding Right Now?

What’s that thing that’s been on your list year after year?

What goal shows up in your head but never in your life?

What are you telling yourself you’ll do “when life is perfect”?

What are you waiting for?

Maybe it’s not a marathon. Maybe it’s starting a business or a blog or learning to paint. Maybe it’s having a tough conversation or writing a book or learning a new skill. Sometimes it’s ending a relationship or beginning one.

Life is really made up of improving upon our failures with constant work and solving the problems seemingly too difficult to face.

Doing this is going to show you who you actually are when things get hard. And that person is probably more capable than you think.

So here’s what I want you to do: Pick one thing. Not three things. One.

And ask yourself the only question that matters: Am I willing?

Am I willing to do it badly?

Am I willing to fail?

Because that’s what it takes. Not readiness or preparation. Just willingness.

And you have that right now.

The question isn’t “Am I ready?” The question is “Am I willing?”

And that seems to be where all the magic is.